A Brief Introduction to Border Interventions

Removing the Curtain

In the mid-1980s, when the effects of neoliberalism began to germinate, and in the 1990s with the agreement of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), borders were opened from point to point for free trade, but not for the free movement of migrants. As a result, a group of artists located between the south of the United States and northern Mexico, together with the migratory communities there, began to re-activate urban spaces through different artistic interventions on the borders. One of the objectives was to question these contradictory socio-political spaces, in which there was a strong presence of control and surveillance that ended in violent encounters. Another aim was to bring to light the calamities of these spaces and thus raise awareness on both sides of the border. This artistic practice has continued until today, dissecting topics such as territories, emigration, xenophobia, surveillance, identity and patriotism.

An example is InSite, an initiative that began in the early '90s, which explored the extraordinary context of Tijuana and San Diego through interventions by different commissioned artists; among these was a performance piece by Venezuelan artist Javier Téllez (2005), an enigmatic work within the history of Border Art. The project was the first time a human cannonball  had been fired across the border with the United States. This happening polemicised the idea of border barriers in the form of "a defiant act that transgresses social and political boundaries literally and figuratively, underscoring the hardships faced by the millions of Mexican and Central American workers who cross the border illegally every year".

1

had been fired across the border with the United States. This happening polemicised the idea of border barriers in the form of "a defiant act that transgresses social and political boundaries literally and figuratively, underscoring the hardships faced by the millions of Mexican and Central American workers who cross the border illegally every year".

1

"The main problem people have at the crossing is their feet. Since people are going to try anyway, at least this will make it safer.” 2

In 2005, if we look at the data, there were 473

3

registered deaths of people who tried to cross the border. The deaths that are documented is always less than the actual number, since only the bodies actually found there count. In response to this humanitarian catastrophe, the Argentine artist Judi Werthein based her work on the specificity of the site and the reality of the emigrant. She designed a pair of mountain shoes  , with motifs based on the symbolism and iconography of this dual culture, that intertwines both territories (eagle motifs and an image of St. Toribio Romo

4

– the patron saint of migrants). This work functioned as a support for migrants: first, they could have some shoes that would help them in their crossing; second, it provided them with tools – a compass, a flashlight and a mini pocket to hide money and medicine – that were essential during the crossing trip; and third, a map printed on the inner sole with the necessary information about the area. The artist sold these shoes as a limited-edition art object in San Diego for a price of $200, money that would be directed in part to the Tijuana shelter for migrants. The project can be read on several levels: if we look at the shoe itself as an object, it has a duality between leaving a mark – a symbol of presence, history and movement – and highlights the difficulty of the path. Once the work was propagated, as a result a group of people responded to the project with criticism

5

– together with racist vocabulary – that makes visible the social imbalance and the symptoms of xenophobia.

, with motifs based on the symbolism and iconography of this dual culture, that intertwines both territories (eagle motifs and an image of St. Toribio Romo

4

– the patron saint of migrants). This work functioned as a support for migrants: first, they could have some shoes that would help them in their crossing; second, it provided them with tools – a compass, a flashlight and a mini pocket to hide money and medicine – that were essential during the crossing trip; and third, a map printed on the inner sole with the necessary information about the area. The artist sold these shoes as a limited-edition art object in San Diego for a price of $200, money that would be directed in part to the Tijuana shelter for migrants. The project can be read on several levels: if we look at the shoe itself as an object, it has a duality between leaving a mark – a symbol of presence, history and movement – and highlights the difficulty of the path. Once the work was propagated, as a result a group of people responded to the project with criticism

5

– together with racist vocabulary – that makes visible the social imbalance and the symptoms of xenophobia.

Both these works, between site-specific art and the confluence of art and activism, are projects within the movement known as Border Art; something essential to underline here is that in this practice of contemporary art there is no modality in terms of means: the movement is instead focused on communicating and raising awareness. We can see in the following examples some of the various practices that have coexisted in this frontera art ecosystem.

Inside WWW

When we think of borders, space itself is of great interest to articulate a work of art, but we must also think about who the audience will be and how it can be democratised for all viewers. In the works that have used an online platform, an example is Tijuana Calling, a group of artists commissioned by InSite_05 6 , which the artist Mark Tribe curated for this online exhibition. This collective of artists explored the correlation between technology as an interactive art tool and technology as a tool of control – as an essential presence in border surveillance.

The use of this medium/format has several advantages in having a broad distribution channel to reach a global audience. Also, the characteristic of being immaterial allows freedom of publication without dependence on institutional bureaucracies in the art world. In interview, Mark Tribe stressed that "the net can enable artists to reach audiences that never set foot in a gallery, museum or performance space.” 7 He commented that today, there are “more and more significant interactions, transactions and experience happening online, so it is a way to engage with audiences in the public sphere”. 8

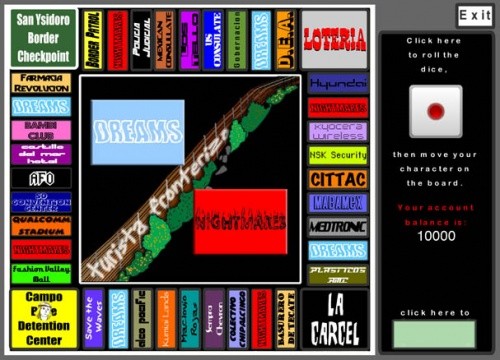

The characteristics that Mark Tribe observes can be seen in the online art project Turista Fronterizo, a work that interactively, humorously and with a sequential narrative portrays real-life controversies and abuses of human rights within this bi-cultural context. This work was born from a collaboration between the multimedia and performance artist Coco Fusco and the hacktivist media artist Ricardo Rodriguez. This bilingual, virtual, interactive project has the appearance of a game board  , similar to Monopoly, or the Mexican version, Tourism. The difference is that the iconography used – the names of places, colours and folk artefacts – is inspired by the border between Tijuana and San Diego.

, similar to Monopoly, or the Mexican version, Tourism. The difference is that the iconography used – the names of places, colours and folk artefacts – is inspired by the border between Tijuana and San Diego.

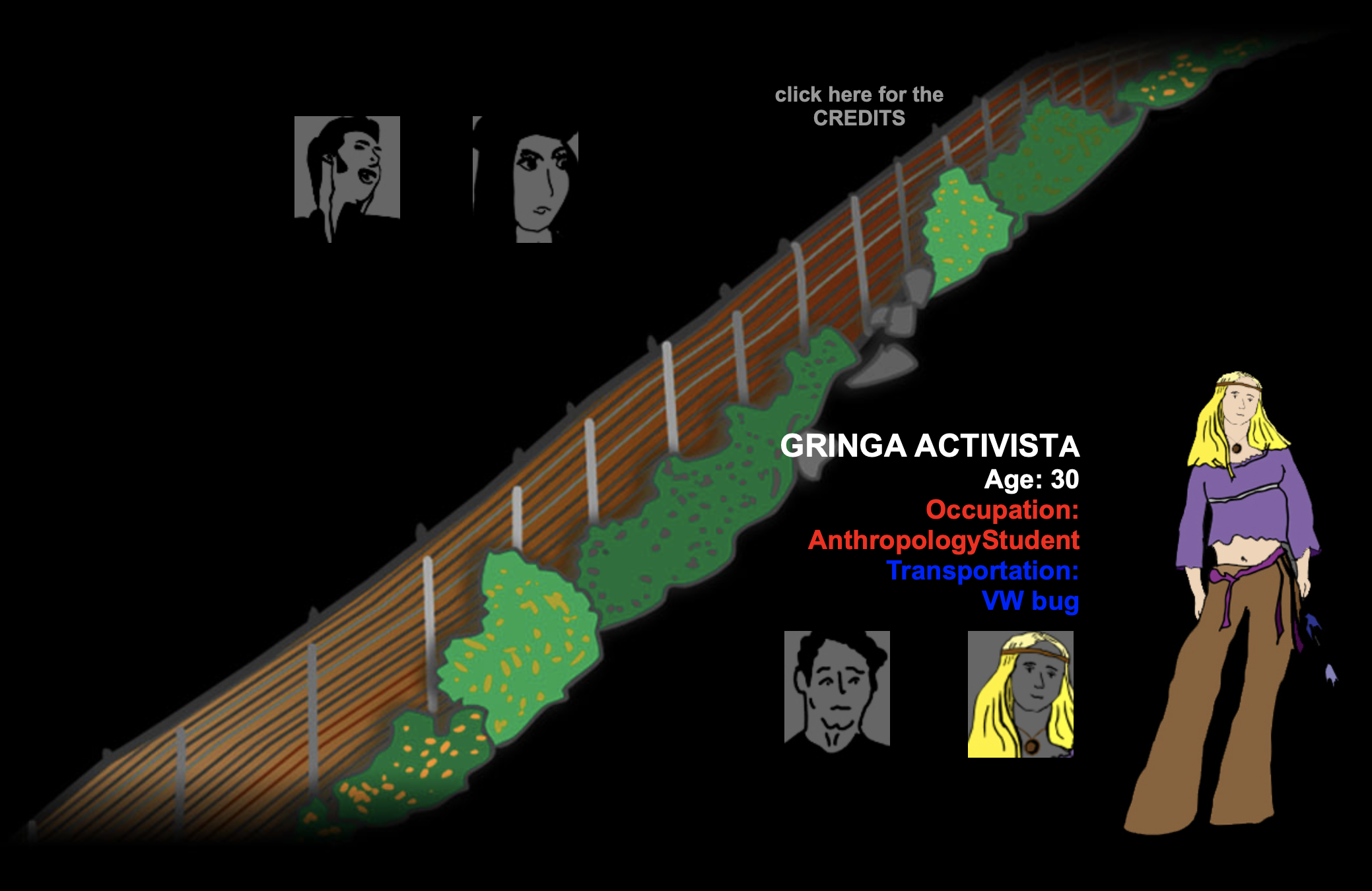

The game is designed in such a way that it is easy to use, designed with basic HTML; therefore it allows all kinds of audiences to interact intuitively. At the beginning, you have an image of the border with a view as if you were looking through a camera – on that plane you can see four individuals  , two Mexicans (“The Junior”, a 25-year-old man, whose profession is “huevón”

9

; his means of transport is a Mercedes G500. Then you have “La Todológa”

10

, a 23-year-old woman whose profession is "everything she finds" – her mode of transport is a Combi.) and two Americans (A powerful gringo

11

, 47 years old – profession: a dual-national businessman; he is transported in his Lexus Sedan. The second character is a 30-year-old "Gringa activist”, a student of anthropology: her means of transport is a VW Beetle). Depending on the role you choose and the language, the experience and perspective you will get through the game will be different. It is not the same experience crossing the border as an American businessman as it is as a Mexican girl in search of work. In the words of Coco Fusco:

, two Mexicans (“The Junior”, a 25-year-old man, whose profession is “huevón”

9

; his means of transport is a Mercedes G500. Then you have “La Todológa”

10

, a 23-year-old woman whose profession is "everything she finds" – her mode of transport is a Combi.) and two Americans (A powerful gringo

11

, 47 years old – profession: a dual-national businessman; he is transported in his Lexus Sedan. The second character is a 30-year-old "Gringa activist”, a student of anthropology: her means of transport is a VW Beetle). Depending on the role you choose and the language, the experience and perspective you will get through the game will be different. It is not the same experience crossing the border as an American businessman as it is as a Mexican girl in search of work. In the words of Coco Fusco:

The more conversant one is in various idioms of the border, the more one can know about all the angles of the game and the more one has access to 'insider' information on both sides of the border. The paths of each player allude to actual experiences that are typical of real life regular border crossers, from elderly Americans who go to Tijuana to buy cheaper prescription drugs medicine, to Mexican day laborers who make their way on foot along Route 5 each day and peddle their skills and trades in San Diego's suburbs. 12

From the first moment you start the game, it opens a window on all the prejudices that exist in the communities that inhabit both sides of the border. Using humour and empathy with the viewer of the work, it creates an awareness of the different life experiences, economic status and difficulties or benefits that each player has. With the simplicity of a game, it allows us to analyse and observe from a cultural and social perspective the humanitarian situation that exists in this specific border. In addition, taking into account the particular limitations of interaction and choice of game, together with the uncertainty of a given, it raises the idea of control, and of geopolitical laws (metaphorically) that end up being a portrait of the lives of these characters. It reminds us of the old saying: life is a gamble.

Inside the White Cube

“Mr Hari, a former sheriff’s deputy, claimed to have compassion for people who try to enter the USA illegally, but said that he submitted his designs for patriotic reasons, telling the Chicago Tribune: ‘We would look at the wall as not just a physical barrier to immigration but also as a symbol of the American determination to defend our culture, our language, our heritage, from any outsiders.;'” 13

When this kind of patriotism exists, the consequences of racism exist – when a person emphasises the word ‘our’: “our culture, our language, our heritage”, defending it from any outsiders. If we all think in this way, then France would need to forge walls with electric gates all around its southern periphery to defend it from Spaniards who are eager to take away their language, culture and heritage.

Crudely, an immigrant is imagined as a poor person, simply because the concept of emigrant or “border crosser" implies a person of low resources. No country wants poor people from abroad to look for work in theirs – this is a reality. The problem is not being an immigrant, but the economic status that the person possesses. Nobody sees Prince Philip as an immigrant – why should this be?

We can see this type of comment and behaviour reflected more clearly in the work of the Mexican artist Yoshua Okón. In Arizona, in 2014, a group called Arizona Border Protectors (AZBD) held one of the largest demonstrations in the United States against migration; the march took place in a small town called Oracle, prompting Okón to start the project. In addition, the name refers to the Oracle Corporation, a transnational company with strong political ties to the CIA. It is a clear example of the "current geopolitical paradigm.”. 14 When we observe the growth of the collusion between government and corporations, we can see a clear reflection of the dominance of private companies over governmental structures that exists, and just as Yoshua tells us in the interview, he is interested in that "enormous contradiction between the global economic system and the nation-state". 15

Okón found this scenario of protesters claiming that there would be an invasion of sixty thousand children from Central America incredibly ironic and contradictory, taking into account the invasions of the United States into Guatemalan territory. This distortion is a portrait of American society that sees only a part of the image. Okón describes this event as "revealing of the nationalist bubble in which most people in the US live. The arrival of these kids to the US is a direct result of the US foreign policy." 16

This four-channel video installation is accompanied by a group of 9 Guatemalan children singing the US Marines' Hymn in chorus. Okón, maintaining the melodic base, modified the lyrics of the anthem, narrating in the song the invading history of the United States after the monopoly between the United Fruit Company and the CIA that took place in the countries on its southern periphery, while the video reflects the recreation of the protest they held in 2014. “The result is a hybrid of documentary and self-parody.” 17 The recordings document these AZ Border Patrol militiamen with an illusory notion of nationalism, which does not exist today. And ironically, it does not exist because of the same effects of the neoliberal doctrine.

"What I argue is that nationalism creates a myopic and limited view of the world, and especially limits on issues of migration." 18

This portrait that Okón provides allows us to see the root causes of the misconceptions we have about migration and transnational policies. Little, or almost nothing, is said about these causes and how they generate as a result of fanaticism: Okón tells us that "they think that is the answer, when in some way nationalism, what they are doing, is exacerbating the problem. To solve it, it is making it more serious, more violent.” 19 This hybrid documentary shows us how this community is seen as "marginals ignored by the system”, hoping to see the nationalist package that the government has promised them: the American dream is non-existent.

In the course of the video, we can see an infinity of references that intensify this reading between the surrealist and the paradoxical, almost quixotic. There is a moment when one of the members of this group drives a Ford truck that drives round in the same circle  – an allegory of nationalism – in the middle of the desert, with a huge flag of the United States, and another that says "Don’t tread on me”

– an allegory of nationalism – in the middle of the desert, with a huge flag of the United States, and another that says "Don’t tread on me”  . This scene, accompanied by bullets to the vacuum-between machine guns and pistols, the sounds of horns and the cry of a retired cowboy’s yee-ha!, demonstrates the absurdity of their struggle. These actions "do not influence anything, but at least they raise dust".

20

. This scene, accompanied by bullets to the vacuum-between machine guns and pistols, the sounds of horns and the cry of a retired cowboy’s yee-ha!, demonstrates the absurdity of their struggle. These actions "do not influence anything, but at least they raise dust".

20

Another scene full of metaphor is the analogy that Okón makes between hoisting the flag in the battle of Iwo Jima, and the raising of the flag with some awkwardness of movement by a group of ex-military in a desert area, giving the impression that they need to plant their identity obsessively, on every stone of US territory, to highlight their patriotic fanaticism. This visual composition, after the buzzing of a fly, turns the scene into a caricatured (involuntary) portrait of this extremist group.

Both the work and the chorus of Guatemalan children were presented for the first time at the Arizona State University Art Museum in Tempe in 2015. This makes it possible to engage an audience that can see the actions of its neighbours in a mirror. One of the questions in the interview with the artist was about the reasons for using these sterile spaces of galleries/art museums to present a project, and what kind of audience is interested in it. Okón says:

Arts spaces are environments typically occupied by the privileged, and it is these people that interest me. This public, in general, does not understand the root causes of migration. The privileged are usually the most conditioned by official narratives, which are totally distorted. Somehow, my goal is to create a short circuit in all your notions, and through my works make people rethink their ideas about reality, and the world, as ideas to subvert from within. For example: I have nothing to explain to the migrants; they already live it day by day, right? 21

Inside the Site

“Make art great again.” 22

In contrast to the two previous projects – online project and gallery / museum-based project – in this project, however, the border space is used as the setting for the work. In this highly sensitive place, Christoph Büchel provokes a polemic, which raises a question about the physicality of national monuments and how such monuments in specific spaces reflect ideologies, beliefs and historical events-whether cruel or not.

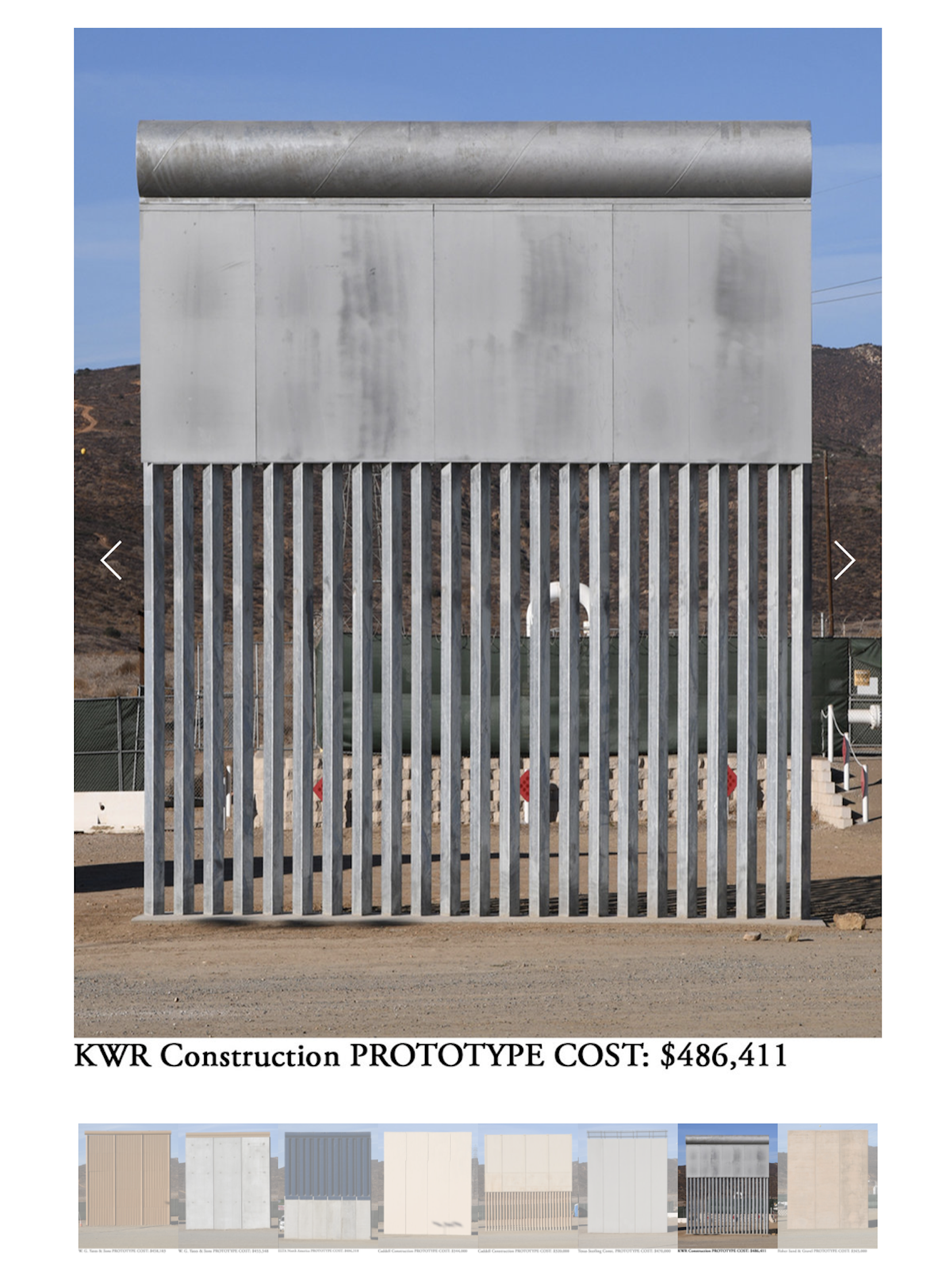

The particular point about this project is that the artist does not create a work in situ, but rather creates a guided tour (for $ 25) to the prototypes  erected by Trump and his followers. The site-specificity is of great importance as they face the wall, which already exists between USA / Mexico, precisely in Otay Mesa, San Diego, California. This data puts in doubt the border reinforcement when a border already exists

erected by Trump and his followers. The site-specificity is of great importance as they face the wall, which already exists between USA / Mexico, precisely in Otay Mesa, San Diego, California. This data puts in doubt the border reinforcement when a border already exists  . This parallel space shows the desire to alienate the 'illegal' immigrant. It also emphasises the ineffectiveness of border barriers.

. This parallel space shows the desire to alienate the 'illegal' immigrant. It also emphasises the ineffectiveness of border barriers.

Büchel - under the aegis of a group called MAGA - names these eight artefacts as "conceptual" sculptures with Land Art qualities, which have a "significant cultural value" in the words of the artist. PROTOTYPES consists of a petition to denominate the eight border wall to a national monument, according to the Antiquities Act of 1906: "legislation that protects natural, cultural, or scientific features on Federal land." 23 The artist clearly demonstrates his intention, preserved and protected from demolition for "all future generations of people."

From the beginning, and at the time of being published, the first visits to PROTOTYPES generated a revolt both at the media level and in the art world. A number of artists started a boycott against Büchel's project and both Büchel's gallery and the international powerhouse, Hauser & Wirth. This group of people named this project as irresponsible and insensitive regarding the suffering of the most vulnerable, who attempt to cross the border. The director of the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York, Gonzalo Casals comments that PROTOTYPES project:

Fails to present a more human and nuanced understanding of the reason those prototypes were created. At this point, as the conversations about the need of a wall are still happening, we need to create platforms for artworks that celebrate the contributions of immigrants to this country, and shed light on the real issues behind the creation of the wall. 24

It is true that this guided tour does not demonstrate the cultural, economic, social, and otherwise significant contributions that immigrants bring to the United States, but it is crucial that we acknowledge that this is because the appreciation of other cultures cannot, and will not be valued until the mental walls have crumbled. It is essential to awaken our conscience and see the monumental absurdity of these prototypes: "monolithic, corporate, severe".

25

In this moment (the 21st century) we must question: What has been the progress from the walls of the Middle Ages to the present? We have invented the meaning of these eight walls ourselves: If these fictions we have created of territorial appropriation and complex political ideologies did not exist then these eight excessively expensive  , theatrical, authoritarian, and fetishistic walls will be only a reminder in the middle of a desert of the constant struggle we have between "us" and "us". The art critic, Jerry Saltz, dissects it in this way:

, theatrical, authoritarian, and fetishistic walls will be only a reminder in the middle of a desert of the constant struggle we have between "us" and "us". The art critic, Jerry Saltz, dissects it in this way:

These prototypes will be a perfect memorial to how close the United States came to giving in to the ghosts of racism, xenophobia, nativism, white nationalism, mediocrity, and a cosmic fear of the other. And this Trumpian monument will stand for this last gasp of the mythical infatuation with race. They will stand as a reminder of how D.H. Lawrence saw America reflected in Moby-Dick: “A mad ship, under a mad captain, in a mad, fanatic’s hunt” afraid of its “white abstract end.” 26

Conclusion. Did a Brick Fall Off?

There is no measurement of impact, nor of effectiveness, on which we can base our assessments to compare and conclude which of these works - Turista Fronterizo; Oracle or PROTOTYPES - had more significant repercussion in this notion of borders. Cuco Fusco was right when she told me by e-mail that: "Art cannot be measured by impact as if it were an earthquake. It often takes years to understand what it means and how it affects the development of art and people.” 27

If we must contrast these three works, we can see how Yoshua Okón's work is more about observation and analysis, for instance, in the behaviour of the protagonists of this video installation: Therefore the audience is passive, unlike the work of Cuco Fusco and Ricardo Dominguez, and in the work of Büchel, in which the audience is active. One merits interaction to be able to unfold the different narratives of the work and in the other, the presence of the audience reinforces the manifesto. While reading critical reviews and articles of the work PROTOTYPES, I found a photo of one of the visits  , which seemed to me in itself an allusion to what Büchel - consciously or unconsciously - wanted to show. If we look at the picture, we see a somewhat raw reality, a certain senselessness. An environment of visible poverty, in front of these monstrous, almost unreal, walls. Visitors with an attitude of tourists. And what most caught my attention, is a man with burlesque laughter, climbing parodically, and on one side a woman (perhaps his mother) making a photo of his occurrence. After seeing this image, I understood that the wall that does not allow us to see beyond is not physical but mental.

, which seemed to me in itself an allusion to what Büchel - consciously or unconsciously - wanted to show. If we look at the picture, we see a somewhat raw reality, a certain senselessness. An environment of visible poverty, in front of these monstrous, almost unreal, walls. Visitors with an attitude of tourists. And what most caught my attention, is a man with burlesque laughter, climbing parodically, and on one side a woman (perhaps his mother) making a photo of his occurrence. After seeing this image, I understood that the wall that does not allow us to see beyond is not physical but mental.

In this thesis, I do not seek to compare the formats used in art, but I do look through the specific, vibrant context of the border between the United States and Mexico, and how these three artists, using these different media, have together sounded the alarm to highlight the issue of migration from different perspectives. Mark Tribe told me: “It is not a question of which art project is more effective than the other: Each one of those are small drops in the ocean, making together an ecosystem of resistance.” 28 Tribe explained to me with a simple analogy, that it is "like a forest that has a great variety of types of trees-the big old trees, the new little sprouts, trees with and without flowers, trees beside the river and trees that makes a nice sound in the wind.” 29 It is the same between these different works: Together, they reinforce these questions and make one have an active and critical position.

In a moment of the interview I had with Yoshua Okón, I asked him if art had the power to break down a border wall? He told me: "We all have a notion of reality that is mostly constructed by the mass media, say official narratives, and art allows us to re-think and question these stories and formulate our own narratives, and this can have an effect on the reality, it can affect the world." 30

With this response, I call on artists and visual communicators to dare to plant trees in this ecosystem of resistance. Visual language has the potential to empathise and reconstruct a universal narrative, on issues that have to be confronted urgently. Currently migration is one of the critical issues that deserve greater attention at the level of government and across the international community. We are in a moment where the violations of human rights have increased the number of migrants dying in their attempts to cross borders to devastating levels (in the USA; in Ceuta/Melilla, Spain and throughout the Mediterranean, to name just a few examples). Visual communication, as we have seen in these three case studies, can raise controversy. It does not matter that they speak well or badly; the important thing is that they speak, and in the end give space to debate, and therefore to progress.